Diagnostic Assessment in Geriatric Mental Health

I. Introductions, nature of students’ practices and interest in the topic, theoretical background and major resources.

II. Cognitive functioning evaluation with diagnostic and treatment implications.

NOTE: It is important to emphasize that the diagnostic implications of various symptoms listed in this handout are the most common psychiatric and neurological ones and by no means exhaustive. They are designed as an illustration of the diagnostic process rather than a reference, which is outside the scope of this relatively brief workshop (it only seems interminable).

1. Overall intellectual functioning.

A. Overall intellectual functioning is important to evaluate for two reasons:

(1) We can estimate Client’s premorbid intelligence and compare current findings to it, to see if there is significant decline in cognition.

– If premorbid functioning was low (e.g. the client had a diagnosis of mental retardation, was a client at the Golden Gate Regional Center, never worked, dropped out of High School, etc.) and current functioning is similarly low, there is no significant change and no change in diagnosis or level of care is indicated, unless additional factors interfere (e.g. Client’s caregiver died or is unable to care for them any more, additional medical problems require increased care, etc.).

– If premorbid functioning was average or above (e.g. the Client was able to complete High School and/or College, kept a job, raised a family, managed their own finances, etc.) and current functioning is only slightly lower, consistent with normal aging, there is usually no need for diagnostic or level of care changes. The diagnosis of Age-related Cognitive Decline can be applied if normative changes start affecting the Client’s ability to function independently.

-If premorbid functioning was average or above and current functioning is significantly lower (note that, in case of significantly above average premorbid cognition, average current functioning implies significant decline) the diagnosis of Dementia or Cognitive Disorder NOS can be considered. The degree of overall decline will determine the appropriate level of care and supervision.

(2) We can compare functioning in specific cognitive domains to it to evaluate for focal cognitive decline. Specific areas of decline determine not only the appropriate diagnosis but also specific interventions.

– If there is decline in memory, but no other areas of cognition, the appropriate diagnosis is Amnestic Disorder and the appropriate intervention could be a memory book or an electronic organizer (see Appendix 1).

– If there is decline in memory and at least one other area, the appropriate diagnosis is Dementia.

– If there is decline in any area or areas of cognition with intact memory, the appropriate diagnosis is Cognitive Disorder NOS.

B. Evaluation of premorbid intellectual functioning:

(1) Informal – by educational, occupational, and daily living skills history.

(2) Formal – similar to informal, but numerically quantified, e.g. Barona’s index or estimated from current test results, e.g. comparing Vocabulary and Abstract Reasoning subtests on the Shipley Institute of Living Scale or Vocabulary and Block design on WAIS-III.

C. Current cognitive functioning evaluation:

The Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) is a brief screening measure most often used in medical settings and will be used as an example throughout this presentation. It is important to note that this is a very simple test detecting only gross disturbances and as such tends to miss early stages of dementia, especially in well educated cognitively active clients. It is also highly age and education dependent, as you can see from the normative data (Crum et al, 1993)

D. Activities of Daily Living:

Activities of daily living (ADLs), as practical reflection of overall cognition, are usually a crucial part of diagnosis and treatment planning. Almost all DSM-IV diagnoses include the criterion stating that “the deficits… cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning”. Their importance for treatment planning and level of care is self-evident. Usually, you will find out about these during the interview with the Client or current caregiver. There is also a variety of formalized measures and questionnaires available in the literature. A typical example is Lawton/Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale (Polisher Research Institute. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL). Available at: http://www.abramsoncenter.org/PRI/documents/IADL.pdf .)

E. Brief Summary of DSM-IV Taxonomy of Acquired Cognitive Disorders:

| Disorder | Etiology | Criteria |

| Delirium | Delirium due to a General Medical Condition | Disturbance of consiousness (awareness)Cognitive or perceptual disturbanceDevelops over a short period (hours to days) and fluctuates during the dayEvidence of physiological cause |

| Substance Intoxication | Same but evidence of a substance being the cause | |

| Substance Withdrawal | Same but evidence of a withdrawal syndrome being the cause | |

| Due to Multiple Etiologies | Same but evidence of multiple etiologies | |

| Dementia | Of Alzheimer’s Type | Memory impairment and one or more other cognitive disturbancesGradual decline from previous level |

| Vascular | Same + focal signs | |

| Due to Head Trauma | Same + frequent amnesia | |

| Due to HIV | Same + frequent tremor, imbalance, ataxia | |

| Due to Huntington’s | Same + choreoathetosis | |

| Due to Pick’s | Same + early personality changes | |

| Due to Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease | Same + myoclonus, periodical abnormal EEG | |

| Due to Parkinson’s | Same, + tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, postural instability | |

| Substance-Induced | Same, lasts longer than withdrawal | |

| Due to Multiple Etiologies | Same, evidence of more than one cause | |

| Amnestic Disorders | Due to a General Medical Condition | Anterograde or retrograde amnesia; Transient if less than 1 month, Chronic if more than 1 month |

| Substance-Induced | Same, due to a particular substance (Alcohol, Sedative, Hypnotic, Anxiolytic, or other) |

2. Level of consciousness.

This is a basic characteristic obvious from a cursory examination. If the Client is not alert (commonly used terms are lethargic, somnolent, obtunded, stuporous, semi-comatose, comatose), an acute medical event (e.g. a transient ischemic attack), an epileptic seizure (in case of brief loss of consciousness) or acute delirium (with an underlying medical event – 293.0, 780.09) are suspected. Usually, no further testing is possible or feasible (since it would not reflect Client’s usual state) until the acute situation is resolved. A commonly used formal way of evaluating the level of consciousness is the Glasgow Coma Scale. (Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 1974,2:81-84.) You can find a detailed article on this scale in Wikipedia.

3. Orientation.

A. Evaluation of orientation:

(1) Informally, orientation can be evaluated in casual conversation, which also saves clients becoming irritated at being asked primitive questions. For example, asking them to sign and date a paper (consent or whatever other paperwork is necessary) and asking how they got there and how was the traffic will usually provide one with a good idea of Client’s orientation.

(2) Formally, on MMSE:

What is the year?

What is the season of the year?

What is the date?

What is the day of the week?

What is the month?

Can you tell me where we are?

What county are we in?

What city/town are we in?

What floor of the building are we on?

What is the name or address of this place?

B. Diagnostic implications:

Significantly impaired orientation implies dementia or severe mental illness, such as psychosis or severe depressive episode.

C. mplications for treatment:

In terms of treatment, the symptom itself is quite easily managed. A wall calendar in a prominent position, with appointments and family or social events marked and (in case of episodic confusion) the Client trained to cross the previous day off every night, is usually sufficient. Alternatively, an electronic organizer (including scheduler with alarm) can be used and offers the advantage of auditory reminders and keeping track of the date automatically. The disadvantage, of course, is having to learn a new technology and forgetting the organizer in various places. A cell phone, palm pilot, pocket PC, or a purpose-built organizer (those are much cheaper, but usually poorly designed and unreliable) can be used.

4. Attention/Concentration.

Attention and concentration are basic characteristics of cognition underlying any other cognitive function. Attention (or simple attention) usually refers to the ability to stay on task without significant active manipulation of information, while concentration (sometimes also called working memory) refers to the ability to manipulate information in one’s mind without loosing it. If attention is significantly impaired, all other areas of cognitive functioning will be detrimentally affected. However, one can partial the effects of attention and concentration problems out by observing the pattern of the Client’s performance. Attention and concentration problems can be compensated for by briefness of tasks, more structure in the instructions, and additional visual or tactile cues. If the client cannot stay on task irrespectively of the time, degree of structure or presence/absence of additional cues, a domain-specific deficit is likely in addition to attention and concentration difficulties.

A. Evaluation of attention and concentration:

(1) Informally, you can see if the client looses the thread of conversation or finds following longer instructions difficult for simple attention. Loosing the thread after interruption or sudden noise is characteristic of concentration problems. If they cannot remember how old they are, providing them with their date of birth (if necessary, though clients usually remember that) and current year and asking to work out their age is a good indicator of gross concentration (e. g.: “You told me you were born in 1915 and it’s now 2007. How old does that make you, then?”.

(2) Formally, you can ask the client to count from 1 to 20 rapidly (simple attention), calculate 2×3, 4×9, do serial 7 [serial subtraction of 7 from 100], and ask how many nickels are in $1.35 (concentration). The MMSE uses three step command to assess attention and spelling a word backwards to asses concentration.

B. Diagnostic implications:

In terms of diagnosis, problems with attention and concentration posses very high sensitivity, but very low specificity – i.e. they appear with (almost) any and all cognitive and mental health problems. If they are the only problem, with otherwise intact cognition and mood, there are two common options:

(1) If they fluctuate significantly over time (as opposed to diurnal fluctuation), medication side effects, an acute infection, a metabolic problem, an endocrine problem, or another physical health issue is likely. Lewy-Body Dementia is sometimes also characterized by this type of fluctuation.

(2) If they do not fluctuate significantly, a focal brain injury affecting central regions of the brain (e.g. reticular activating system) should be suspected.

C. Implications for treatment:

In terms of preserving or restoring one’s ability to concentrate, sustained mental activity is crucial. Working in some form, following through with an active hobby, or doing crosswords, logic puzzles, computer games involving concentration (solitaire, chess, puzzle games), etc. is very helpful.

Specific techniques of attention rehabilitation can involve:

(1) Verbal mediation (algorithmization and talking oneself through the task).

(2) Repetition (repeating and paraphrasing the information).

(3) Reducing interference (eliminating distractions).

(4) Increasing salience of information (emotional – by focusing on important outcomes or cognitive – by structuring or relating information in familiar ways).

In terms of compensating for inability to concentrate, increase in structure is crucial, with the level of structure dependent on the degree of attention and concentration problems. For example, if the person looses track of the recipe while cooking, posting a written copy of the recipe next to the cooker may be sufficient. If they tend to forget what they were doing and wander off while leaving the stove on, but are aware of that tendency, training them to always use a timer on the stove may do the trick. If, however, they are not aware that they do that (which is probably an indicator of a more severe problem), a placement somewhere where their meals are cooked and they have no access to dangerous appliances may be in order.

5. Language Functioning.

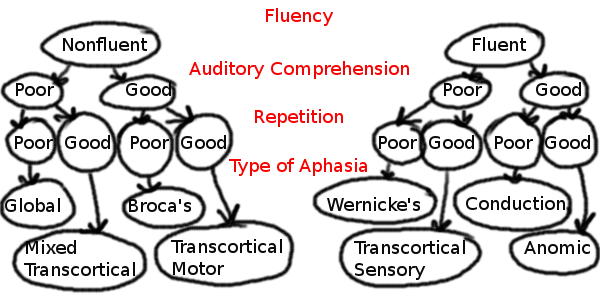

There is a variety of classifications of aphasias or primary language disorders. A common one is presented below (Beeson and Rapcsak, 1998):

A. Evaluation of language functioning:

Aphasias are usually characteristic of left hemisphere brain damage and dementias. Informally, just listening to your interlocutor is usually sufficient in terms of expressive language and noticing if they understand your questions or instructions – in terms of receptive language. Formally, MMSE uses object naming, repetition, reading, writing, and three step command tasks to evaluate language functioning. We are looking for:

(1) anomia/dysnomia: three step testing can be used with any stimulus set – (a) confrontation naming (show an object, ask what it is), (b) responsive naming (ask for name giving a functional description – stimulus cue), and (c) try phonemic cue (give the beginning of the word);

(2) Verbal fluency: norm is 100-200 words/min., considered low for less than 50 words/min.;

(3) Writing fluency: (phonemic fluency problems – anterior lesions, semantic – posterior);

(4) Repetition;

(5) Seriatim speech = speech that rhymes or goes in predictable order (say numbers or repeat rhymes);

(6) Agrammatism (telegraphic speech);

(7) Scanning speech = slow, prosody impaired;

(8) Dysarthria = problems with motor components of speech;

(9) Dysgraphia = problems with motor component of writing;

(10) Dyslexia = problems with reading;

(11) Paraphasias: literal (phonemic – dropping, transposing, or substituting similar sounds), verbal (semantic – substitution of a semantically related word), extended (word salad), neologism (extended paraphasia for one word);

(12) Circumlocutions;

(13) Stuttering (repeating first part of word or phrase);

(14) Pallilalia (repeating last part of word or phrase);

(15) Echolalia.

B. Diagnostic implications:

(1) speed: slow (depression, psychomotor retardation due to brain injury, very mild expressive aphasia), fast (mania, anxiety);

(2) unusually high/low pitch (mild dysarthria due to CNS damage or peripheral nerve damage);

(3) bad articulation (dysarthria due to CNS damage or peripheral nerve damage, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, speech apraxia);

(4) content: coprolalia (Tourette’s), echolalia, incoherent, logorrhea, mute, stilted, neologisms, clang associations, word salad (usually thought disorder, though may be severe expressive aphasia), circumlocutions, semantic substitutions (word finding problems common in dementias and expressive and conductive aphasias), paraphasic errors, agrammatism (expressive aphasia), telegraphic speech (Broca’s aphasia);

(5) fluency: pressured, garrulous (mania), taciturn (depression, dementia), stammering, stuttering (anxiety), slow and labored (Broca’s);

(6) poor comprehension without any other cognitive or emotional symptoms or in only one modality – e.g. poor auditory comprehension with intact reading (receptive aphasia);

(7) repetition (expressive aphasia);

(8) naming: confrontational & responsive (expressive aphasia, word finding problems);

(9) reading (receptive agraphia);

(10) writing (agraphia).

C. Implications for treatment:

For aphasias proper, a referral to a speech therapist is recommended. Depending on the degree and type of aphasia they may suggest:

(1) Receptive: write if aphasia is aural only, use dictation software if it is agraphia, otherwise use simple language and ask the Client to repeat instructions just heard to ensure understanding, in more severe cases use pictures and gestures.

(2) Expressive: the Client can write, use phrase/word/picture cards, letter boards, speech synthesizer, Lyngraphica, etc. You can also formulate your questions in such a way that they only require yes/no answers (or nodding/shaking head).

6.Visual-Spatial Functioning.

Here we are looking for visual misperceptions, visual neglect and constructional dyspraxia. Peripheral vision problems, such as far/nearsightedness can be ignored if the vision is sufficient to accurately perceive the stimuli or sufficiently corrected by glasses.

A. Evaluation of visual-spatial functioning:

(1) Informally one can check if the client can read, if they read the entire page (without, for example, ignoring its left side), if they recognize objects in the room, walk without deviating to one side and dress without forgetting buttons or buckles on one side.

(2) Formally, MMSE asks one to copy two intersecting pentagons.

B. Diagnostic implications:

(1) Apart from peripheral nerve damage, visual misperceptions and visual neglect are usually indicative of focal brain damage to the primary and secondary visual areas of occipital cortex and constructional dyspraxia is characteristic of right anterior cortex injury.

(2) Dementias are often characterized by constructional dyspraxia, but rarely by visual misperceptions or neglect.

(3) Visual illusions and hallucinations are often indicative of organic psychoses, as opposed to schizophrenia-spectrum thought disorder.

C. Implications for treatment:

(1) The most dangerous common consequences of visual misperception and neglect involve walking into obstacles with resultant falls. Using a walker (even with a steady gait) to stabilize the Client in case of walking into an obstacle often works. Otherwise cognitively intact clients can be taught to consciously scan the side they neglect by physically turning their head.

(2) In terms of reading, using a ruler under each line and making sure to scan the page or using computer software which reads the text would usually work. Constructional dyspraxia rarely presents a practical problem.

7. Executive Functioning.

This is a broadly (and rather poorly) defined area of cognition involving “higher cognitive processes” such as organization, planning, reasoning and problem-solving. Ability to make informed medical decisions is an especially important area here.

A. Evaluation of executive functioning:

(1) Informally capacity to make informed decisions, reasoning, judgment and insight could be summarily assessed by engaging the Client in the conversation about his or her current health status, treatment options and related decisions. It is important to use a concrete example and ask the Client for his or her reasoning, rather than just a conclusion.

(2) Formally, the clock drawing test is often used: “I want you to draw the face of a clock with all the numbers on it. Make it large. Please, set the time to 10 after 11.” (Goodglass and Kaplan, 1983)

(3) For formal assessment of capacity to make informed decisions, I would recommend the Hopkins’ Competency Assessment Test (Janofsky, McCarthy and Folstein, Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 1992)

B. Diagnostic implications:

Significant executive functioning disturbances imply anterior brain damage, massive diffuse brain damage, dementia, delirium or psychosis. While depression sometimes gives the impression of executive disturbance because of lack of motivation, it can usually be negated by structuring the task and asking yes/no questions.

C. Implications for treatment:

Since executive functioning deficits are global and affect self-assessment, reasoning and decision-making across the board, structural interventions are most effective. Once again, depending on the degree of impairment, the Client may need help and supervision in novel situations only, with his or her life otherwise arranged to be as routine as possible, or the Client may need 24-hour supervision and placement on a locked unit. Executive functioning deficits, especially perseveration, disinhibition and loss of ability to monitor one’s own behavior as well as the ability to come up with alternative solutions (leading to rigid reactions) are responsible for most behavioral problems.

Case examples: hoarding behavior and resistance to care.

III.Sensory-motor and memory functioning evaluation with diagnostic and treatment implications.

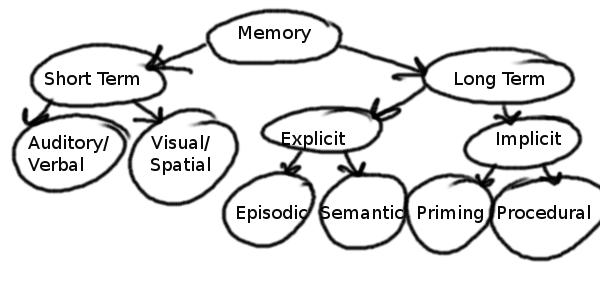

1. Memory Functioning.

Memory functioning evaluation is crucial for the diagnoses of dementia and amnesitc disorder. There exist a variety of models of memory. One of the typical ones looks like that (Strauss, Sherman and Spreen, 2006):

In terms of diagnosis, we are only really interested short term and explicit semantic long-term memory. Ideally, we want to check short term verbal and non-verbal memory for all areas:

(1) encoding;

(2) retrieval;

(3) cued response;

(4) recognition;

(5) immediate recall;

(6) delayed recall.

A. Evaluation of memory functioning:

(1) Informally, remote memory can be (and is best) evaluated during the interview. When client is asked about his or her history, it is important to include the whole time line to observe the pattern of memory loss. Temporal information (such as dates and relative positioning of events) seems to go first.

(2) Formally, MMSE uses three words to evaluate short-term immediate and delayed memory, as well as cued response and recognition. However, because of the small number of words and brief delay, MMSE only detects very gross memory disturbances, usually appearing when dementia is quite advanced and, frankly, obvious without any testing. To diagnose dementia early, supraspan memory testing is used for both auditory and visual modalities. The results are then compared with age and education-appropriate data, since both affect normal memory span to a significant degree. A typical example is the Word List Memory test created by the Consortium to Establish a Registry for the Alzheimer’s Disease (best for the geriatric population, now sold by Duke at http://cerad.mc.duke.edu/ ) or Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning and Complex Figure Tests, which are public domain tests and therefore presented for demonstration purposes.

B. Diagnostic implications:

In terms of the pattern of remote memory loss:

(1) In gradually progressing dementias, both cortical and subcortical (e.g. Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s), the pattern of memory loss has a typical gradient, with better memory for remote history and poorer memory for recent history.

(2) In abrupt onset dementias (e.g. dementia due to a traumatic brain injury) or dementias with stepwise progression (e.g. vascular dementia), you can observe abrupt or stepwise decrease in actual memories and often corresponding increase in confabulation and paranoid ideation. It is important to note that sudden environmental changes, such as death of a partner or move to another living situation, mimic abrupt memory loss, since structure allowing the Client to function in spite of memory loss has disintegrated.

(3)In amnestic disorder (organic rather than psychogenic) there is usually a sharp cutoff when the new memories are no longer formed as efficiently. It is usually associated with some form of anoxic event. If recent research on long-term effects of major surgery on geriatric patients is confirmed, there could also be a “stepwise” form of amnestic disorder, associated with multiple surgeries with general anesthesia.

To summarize the diagnostic features of dementias (from Fields, Robert B., 1998):

| Type of dementia | Onset and course | Neuropsychological features |

| Alzheimer’s (AD) | Insidious onset and progressive deterioration, early onset is associated with genetic causes and rapid course. | Memory deficits across the board and executive dysfunction appear early, global deterioration follows. Indifference, impulsivity, limited insight, restlessness and mood-independent delusions appear later in the course of AD. |

| Vascular | Average onset earlier than AD, can be abrupt or stepwise (strokes) or gradual (small vessel ischemic disease). | Focal deficits corresponding to the location of strokes, focal neurological signs, palsy, gait disturbances, weakness and sundowning more common than in AD. |

| Lewy-Body Disease | Onset similar to AD, but more rapid course. | Relatively greater deficits in attention, visuospatial and constructional skills, psychomotor speed and verbal fluency, mild Parkinsonian symptoms (bradykinesia, masked facies and gait abnormality, but not extreme rigidity, flexed posture or resting tremor), and earlier and more prominent visual hallucinations than AD. Increased sensitivity to extrapyramidal side effects and significant fluctuations in cognition on a daily basis are specific to this syndrome. |

| Frontotemporal | Earlier onset and more rapid course than AD, progressive course. | Starts with executive dysfunction (regulatory deficits leading to perseveration, disinhibition, inflexibility, and problems with organization, planning and abstraction) while other areas of cognition are relatively intact. Gradually memory, language and selective attention deficits develop. |

| Subcortical | Onset and course vary (e.g. Huntington’s at 35-45, Parkinson’s at 70es). | Relatively better recognition memory than recall and better response to cueing, more impairment in executive functioning, visuospatial skills and motor speed and less in language than AD. Bradyphrenia (slowed thinking), gait and balance disturbances, movement disorders and dysarthria are prominent. |

| Delirium | Abrupt onset and fluctuating course. | Global deficits due to fluctuation in arousal, attentional and executive dysfunctions are prominent, visual and tactile hallucinations are common. |

| Pseudodementia in depression | Cognitive symptoms develop and fluctuate with depressive symptoms. | Variable test performance with poor motivation, deficits in attention ad free recall, but not recognition, language, visuospatial or sensory-motor functioning (except for psychomotor retardation). If hallucinations or delusions are present, they are mood-congruent. |

C. Implications for Treatment:

To improve memory:

(1) First of all we need to improve initial encoding. Improving concentration on the material at hand (see attention section above), multimodal input (writing the information down, reading it aloud and providing pictorial or spatial cues, such as in the method of loci) and structuring it in a familiar way as much as possible (categorization, counting the number of items or steps, chunking, forming associations with familiar information by constructing analogies or noting differences) all are helpful.

(2) Second, we need to improve storage and retention. Practice and repetition are crucial for this step.

(3) Finally, to improve retrieval, structural (e.g. using the shop isles to recall what needs to be bought, going through the alphabet to recall a list of words, etc.) and environmental (e.g. learn information in the environment you will need to recall it in, imagine retracing your steps, etc.) cues can be used.

In addition to external memory aids, such as memory books and electronic organizers described above, maximizing routine and structure (which decreases the need for explicit memory) is essential to manage memory deficits. Organizing things (e.g. putting all cutlery in one drawer, etc.) and labeling all drawers and containers prominently usually helps. Notes and reminders, including checklists, can also help compensate for memory loss. For example, it often helps to put a checklist on the door with all important reminders for what to do before leaving (i.e. turn off the stove, water, etc.).

Behavioral disturbances related to memory loss most commonly involve wandering (and getting lost) and paranoia.

Wandering Behavior Management Example.

Paranoid Ideation Management Example

2. Motor Functioning.

A. Evaluation of motor functioning:

Involuntary movement disorders (Dyskinesias) are usually obvious upon observation:

(1)Tremor – rhythmic movement, resting, action or postural (against gravity);

(2)Chorea – asynchronous movement;

(3)Ballismus – unilateral choreiform movement;

(4)Dystonia – prolonged muscle contraction causing abnormal posture or repetitive movement;

(5)Tic – repetitive transient stereotyped movements;

(6)Athetosis – peripheral dystonic movements, “writhing”;

(7)Myoclonus – brief involuntary muscle contractions (subcortical lesions usually produce generalized myoclonus, while cortical lesions produce a focal presentation);

(8)Fasciculation – twitches beneath the skin.

Voluntary movement disorders (Apraxias):

(1) In general terms, we look at “how to do things” system, “when to start/stop” system, and praxicons (voluntary movement sequences representations):

(2) For “how to do things” system (praxicons) we assess transitive (with tools) & intransitive movements for both hands in three stages – 1) pantomime to command, 2) pantomime to imitation, & 3) do it with the object – look for content errors (semantic) and production errors (temporal & spatial):

– Limb or melokinetic apraxia (fine finger movement problems – corticospinal);

– Ideomotor – problems with transitive acts to command (spatial & temporal production errors, body part as object errors);

– Conduction – cannot do pantomime to imitation only;

– Disassociation – cannot do to verbal command only;

– Ideational – problems with sequencing of movements only (Alzheimer’s, large frontal lesions);

– Conceptual – content-related errors to command and imitation;

(3) For “when to start/stop” system:

– Akinesia – not being able to perform a sequence when the person knows how to do it;

– Hypokinesia – takes long to initiate movement;

– Motor extinction – can do movements with each hand separately, but have problems coordinating them;

– Motor impersistence – response is weakening fast;

– Defective response inhibition (typical in Huntington’s);

– Motor perseveration;

(4) Additional terms:

– Bradykinesia (slowed execution of movement);

– Constructional apraxia (trouble with drawing);

– Dress apraxia (mix up clothing while getting dressed).

B. Diagnostic implications:

– Parkinsonism (tremor+rigidity+bradykinesia+postural abnormalities) is a syndrome caused by a variety of different conditions, including neurodegenerative (Parkinson’s disease, olivopontocerebellar atrophy, Shy-Drager syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy, striatonigral degeneration, corticobasal ganglionic degeneration, Parkinson-ALS-dementia complex of Guam, pallidoponto-nigral degeneration, dentato-rubro-pallido-luysian atrophy, Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy-body disease, Huntington’s disease, Pick’s disease, Fahr’s disease, multiple sclerosis, neuroacanthocytosis), metabolic (Wilson’s, Gaucher’s, Hallervorden-Spatz, GM, gangliosidosis), infectious (Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, viral encephalitis, syphilis, encephalitis lethargica, HIV, sarcoid, toxoplasmosis, cryptococcosis), traumatic (dementia pugilistica), structural (hydrocephalus, chronic subdural hematoma, arteriovenous malformations, tumors), vascular (basal ganglia infarcts, amyloid angiopathy, Binswanger’s disease), toxin-induced (manganese, mercyry, carbon monoxide, carbon disulfide, cyanide and MPTP poisoning), lithium and neuroleptic side effects, and factitious and somatoform disorders (from Koller et al, 1994).

– Parkinson’s disease (PD) proper usually becomes symptomatic in one’s 60es; cognitive abnormalities usually involve executive dysfunction caused by frontostriatal damage; dementia is reported in 20-40% of the cases and involves memory, attention, visuospatial and executive dysfunctions, with preserved language and praxis – a “typical” subcortical dementia.

– Some Parkinson-plus syndromes:

(1) Progressive supranuclear palsy (symptoms are typically symmetrical at onset, as opposed to PD, resting tremor is minimal and postural imbalance is significant early symptom; dysarthria may appear early, later there is usually prominent gaze palsy, disproportionate axial rigidity, prominent gait disturbance, facial spasticity, impairment of saccadic eye movements, dementia reported in 50-80% of the cases);

(2) Multiple system atrophies (heterogeneous group characterized by early cerebellar ataxia which progresses gradually, other symptoms, including dementia, vary);

(3) Corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (insidious late onset, early akinesia and rigidity, asymmetrical early presentation with one arm or leg being clumsy, stiff and jerky, dementia is reported to occur late with both subcortical and cortical features).

– Wilson’s disease is a disorder of copper metabolism usually presenting between 8 and 16 with dysarthria, poor coordination, and sometimes postural abnormalities, dystonia, chorea and parkinsonism, as well as liver disease and copper corneal rings.

– Huntington’s disease usually presents in 30es-40es (though there is a juvenile form), starts with personality changes and adventitious movements evolving into chorea, subcortical dementia is common and develops later.

– Multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating disorders show a great variety of symptoms, including sensory disturbances, weakness, gait and balance disturbances, dysarthria, and sometimes cognitive changes, they remit and reoccur at varying intervals.

C. Implications for treatment:

Falls and limitations in motor control are the biggest problems. In addition to medications, bars, mobility aids and physical therapy, it helps to keep the floors clear of rugs and furniture and to ensure that the client wears non-skid socks and rubber-soled shoes.

3. Sensory Functioning.

Here we are looking for visual misperceptions, visual neglect and constructional dyspraxia. Peripheral vision problems, such as far/nearsightedness can be ignored if the vision is sufficient to accurately perceive the stimuli or sufficiently corrected by glasses.

A. Evaluation of sensory functioning:

In general terms, agnosias are divided into apperceptive (stimulus does not translate into accurate percept) & associative (percept is there, the problem is with attributing meaning to it) types;

(1) Somesthetic agnosias: Agraphesthesia (inability to distinguish shapes written on skin); Somatolopagnosia (inability to say whuich part of one’s body was touched); Astereognosis (inability to discriminate objects gby touch);

(2) Auditory agnosias: Aphasia; Amusia; Arhythmia; Aprosodia; Environmental (sounds which carry meaning, like fire alarm);

(3) Visual agnosias: Object; Facial (Prosopagnosia); Metamorphosia (change in object size while looking); Megalopsia (increase in object size); Prosopoaffective (inability to recognize consensual meaning in facial expressions); Visual/verbal (dyslexia);

(4) Gustatory agnosia = Ageusia;

(5) Smell = Anosmia.

B. Diagnostic implications:

Global agnosias imply fairly easily localized CNS damage, with apperceptive agnosias resulting from damage to the primary perceptual area of the cerebral cortex and associative agnosias resulting from the damage to secondary and tertiary areas or connecting axons. Some types of hallucinations may mimic agnosias, but this type of hallucinations is also characteristic of organic, rather than functional, disturbances. Peripheral nerve damage usually results in focal disturbances in sensation, e.g. dermatoma-shaped somesthetic agnosias, visual field cuts, etc..

IV. Emotional and personality functioning evaluation with diagnostic and treatment implications.

A. Evaluation of emotional functioning:

– Emotional functioning evaluation in geriatric population is usually conducted during a standard clinical interview.

(1) One of the special considerations relevant here is the fact that less educated older clients tend to be less psychologically minded and may not be aware of psychology-related jargon which by now became the part of the mainstream culture. Thus, focusing on behavioral descriptions of specific symptoms, rather than general diagnostic terms, tends to be more productive. For example, rather than asking “Are you depressed?” one may ask: “How often do you feel sad? Cry? Fell low energy?”, etc.

(2) It is also extremely important to rule out physical causes of symptoms before considering psychiatric diagnoses in this population, since delirium often presents with psychotic symptoms and multiple disorders present with some symptoms of depression and anxiety. Thyroid and other endocrine disorders, vitamin B and other nutritional deficiencies, electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, liver and kidney problems, acute infections, especially urinary tract infections, diabetes mellitus, etc. are common rule-outs.

(3) Differentiating between normal reaction to loss, both interpersonal and functional, and psychiatric illness, becomes increasingly important in this population.

– Formal evaluation techniques commonly used in geriatric population consist of screening questionnaires. Unfortunately, only depression is commonly assessed. The Geriatric Depression Scale is typical and often used public domain test for clients who can answer these questions (This scale can be found on Dr. Yesavage’s page at www.stanford.edu). If the client is unable to answer this type of questions for any reason, observational measures are often used. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale is a good example (from Hedlung and Vieweg, (1979). The Hamilton rating scale for depression, Journal of Operational Psychiatry,10(2), 149-165)

B. Diagnostic implications:

Below, you will find a brief summary of DSM-IV criteria for major psychiatric conditions. I did not include personality disorders, since these are usually not diagnosed in geriatric population. While certain personality characteristics may (and usually do) become relevant, determining preexisting life-long patterns of behavior becomes difficult, especially if significant cognitive changes complicate the clinical picture.

| Grouping | Disorder | Criteria |

| Psychotic Disorders | SchizophreniaTypes: Paranoid, Disorganised, Catatonic, Undifferentiated, and Residual | 1)For at least 1 month, 2 or more of:- delusions,- hallucinations,- disorganized speech,- grossly disorg./catatonic behavior,- negative symptoms (affective flattening, alogia, avolition)2) Lasts 6 months or more |

| Schizophreniform | Same, but lasts 1 to 6 months | |

| Brief Psychotic | Same, but lasts 1 day to 1 month | |

| Schizoaffective | Same, but psychotic symptoms are present concurrently and for at least 2 weeks longer than a Major Depressive, Manic, or Mixed Episode | |

| DelusionalTypes: Erotomanic, Grandiose, Jealous, Persecutory, Somatic, Mixed, and Unspecified | 1)Nonbizarre delusions2)Last for 1 month or more3)Functioning not impaired apart from direct impact of delusions4)If there is mood episode, it is brief compared to delusions | |

| Shared Psychotic | A delusion similar to one a close person has develops in context of that relationship | |

| Due to a Gen. Med. Cond. | Hallucinations or delusions due to Med. Cond. | |

| Substance-Induced Psychotic | Hallucinations or delusions due to substance | |

| Mood DisordersSpecifiers: Severity/Psychotic/Remission, Chronic (>2 years), with Catatonic, Melancholic, Atypical features, with Postpratum Onset, with Seasonal Pattern | Major Depressive Episode | 1)Either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in most activities2)Four (three if both) or more of:- change in weight or appetite- insomnia or hypersomnia- psychomotor agitation or retardation- fatigue or loss of energy- feeling of worthlessness or excessive guilt- diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness- recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation3)Symptoms present for 2 weeks or more4)Symptoms represent a change from previous functioning |

| Manic Episode | 1) A distinct period of abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood2) Three or more (four or more if only irritable) of:- inflated self-esteem or grandiosity- decreased need for sleep- more talkative or pressure to keep talking- flight of ideas or experience of thought racing- distractibility- increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation- excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences3) Lasts 1 week or more (less if hospitalization required) | |

| Mixed Episode | 1) Criteria are met for both Manic and Depressive Episodes2) Lasts for 1 week or more | |

| Hypomanic Episode | 1)Symptom criteria the same, as for Manic Episode2)Lasts at least 4 days3)Changes in mood and functioning are observable by others4)No marked impairment in social or occupational functioning, need for hospitalization, or psychotic features | |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 1)Major Depressive Episode (at least two months interval between episodes for Recurrent)2)Never a Manic, Mixed, or Hypomanic Episode | |

| Dysthymic Disorder | 1) Depressed mood most of the time2) 2 or more of:- insomnia or hypersomnia- poor appetite or overeating- low energy or fatigue- low self-esteem- poor concentration or difficulty making decisions- feelings of hopelessness3) Lasts 2 years or more (1 for children)4) No more than 2 months without symptoms5) No Major Depressive Episode these 2 yrs6) Never Manic, Mixed, or Hypomanic Episode | |

| Bipolar I | One or more Manic or Mixed Episodes, may have Depressive Episode (or not) | |

| Bipolar II | 1)One or more Major Depressive Episode2)One or more Hypomanic Episode3)Never a Manic or Mixed Episode | |

| Cyclothymic | 1)Numerous periods with hypomanic and depressive symptoms2)Lasts 2 years or more (1 for children)3)No more than 2 months without symptoms4)No Major Depressive, Manic, or Mixed Episode these 2 yrs | |

| Anxiety Disorders | Panic Disorder With Agoraphobia(If only Panic or only Agoraphobia, code: Panic Disorder Without Agoraphobia or Agoraphobia Without History of Panic Disorder) | 1)Recurrent unexpected Panic Attacks or discrete periods of fear or discomfort with 4 or more symptoms developing abruptly and reaching a peak within 10 minutes:- palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate- sweating- trembling or shaking- feeling of shortness of breath or smothering- feeling of choking- chest pain or discomfort- nausea or abdominal distress- feeling dizzy, unsteady, lightheaded, or faint- derealization or depersonalization- fear of loosing control or going crazy- fear of dying- paresthesias (feeling of numbing or tingling)- chills or hot flashes2)At least one attack was followed by 1 month or more of 1 or more of:- persistent concern about having additional attacks- worry about the implications or consequences of attacks- significant behavioral change related to attacks3)Presence of Agoraphobia, characterized by:- anxiety about being in places or situations from which escape may be difficult or embarrassing or in which help may not be available in the event of panic symptoms- these situations are avoided, endured with marked distress, or require presence of a companion |

| Specific PhobiaTypes: Animal, Natural Environment, Blood-Injection-Injury, Situational, Other | 1)Persistent, excessive fear cued by the presence or anticipation of specific object or situation2)Immediate anxiety response to phobic stimulus3)The person recognizes that fear is excessive or unreasonable (not necessary in children)4)The stimulus is avoided or endured with intense anxiety5)In children under 18 lasts 6 months or more | |

| Social Phobia | Same as specific phobia, phobic stimuli are social or performance situations in which one is exposed to unfamiliar people or scrutiny by others and fears that one will act in an embarrassing way. | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 1) Either Obsessions:- recurrent thoughts/impulses/images that are experienced as intrusive and inappropriate and cause marked anxiety and distress,- and thoughts/impulses/images are not just excessive worries about real life problems,- and person attempts to ignore/suppress/neutralize these thoughts/impulses/images,- and person recognizes that thoughts/impulses/images are a product of his/her own mindor Compulsions:- repetitive behaviors or mental acts that one feels driven to perform in response to obsessions or according to rigid rules- and these acts are aimed at preventing distress or an event, while either not realistically connected to that event or clearly excessive2) At some point during the disorder the person has recognized that obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable (not necessary in children) | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 1) The person has been exposed to a traumatic event where he/she experienced actual or threatened death or serious injury or threat to physical integrity of him/her or other and the person responded with intense fear, helplessness, or horror (in children could be disorganized/agitated behavior)2) The event is reexperienced in 1 or more of:- recurrent intrusive recollections (play in children)- recurrent dreams (in children may be vague)- flashbacks/reenactment- intense distress in response to cues symbolizing it- physiological reactivity in response to these cues3) Avoidance of stimuli associated with trauma and numbing of general responsiveness as indicated by 3 or more of:– avoiding thoughts/feelings/conversations about it- avoiding activities/places/people associated with it- inability to recall important aspects of the trauma- diminished interest or participation in significant activities- feeling of detachment or estrangement from others- restricted range of affect- sense of foreshortened future/p>4) Increased arousal as indicated by 2 or more of:- difficulty falling or staying asleep- irritability or angry outbursts- difficulty concentrating- hypervigilance- exaggerated startle response5) Lasts over a month (Acute if 1-3 months, Chronic if more than 3) | |

| Acute Stress Disorder | Same as PTSD, but duration is 2 days to 4 weeks and has to occur within 4 weeks of the event. Also, has to have 3 or more of dissociative symptoms, including:1) Sense of numbing/detachment/emotional unresponsiveness Sense of numbing/detachment/emotional unresponsiveness2) Reduction in awareness of one’s surroundings3) Derealization4) Depersonalization5) Dissociative amnesia | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 1)Excessive anxiety and worry about a number of events for 6 months or more2)One finds it difficult to control the worry3)Three or more of (only 1 in children):- restlessness or feeling on edge- being easily fatigued- difficulty concentrating or mind going blank- irritability- muscle tension- sleep disturbance | |

| Somatoform Disorders | Somatization Disorder | 1) History of numerous physical complaints resulting in seeking treatment or significant impairment2) Begins before 30 years and lasts for several years3) All of the following symptoms:- 4 pain symptoms- 2 gastrointestinal symptoms- 1 sexual symptom- 1 pseudoneurological symptom4) Symptoms are not explained by medical condition and not intentionally feigned |

| Undifferentiated Somatoform Disorder | Same as Somatization, but only requires 1 or more physical symptoms and lasts 6 months or more | |

| Conversion Disorder | 1)One or more voluntary motor or sensory disturbance2)Psychological factors are judged to be associated with it3)Symptoms are not explained by medical condition and not intentionally feigned | |

| Pain Disorder (Acute if less than 6 months, Chronic if more than 6) | 1)Pain is the focus of clinical presentation2)Psychological factors are judged to be associated with it3)Pain is not totally explained by medical condition and not intentionally feigned | |

| Hypochondriasis | 1)Preoccupation with having a serious disease based on misinterpretation of bodily symptoms2)Preoccupation persists despite medical evaluation, but is not of delusional intensity3)Lasts 6 months or more | |

| Body Dysmorphic Disorder | Preoccupation with imaginary defect in appearance or exaggerated preoccupation with slight physical abnormality. | |

| Factitious Disorders | Factitious Disorder | 1)Intentional feigning of physical or psychological symptoms2)Motivation is assuming sick role and not external incentive |

| Dissociative Disorders | Dissociative Amnesia | Predominant disturbance is inability to recall important personal information associated with trauma. |

| Dissociative Fugue | Sudden travel away from home or work with inability to recall one’s past and confusion about one’s identity or assumption of a new identity | |

| Dissociative Identity Disorder | 1) 2 or more distinct identities2)At least 2 of them recurrently control behavior3)Inability to recall important personal information | |

| Depersonalization Disorder | Persistent or recurrent experiences of depersonalization (detachment from one’s body or mind) with intact reality testing | |

| Sexual and Gender Identity DisordersSpecifiers: Lifelong/Acquired, Generalized/Situational, Due to Psychological Factors/Due to Combined Factors | Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder | Persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity |

| Sexual Aversion Disorder | Persistent or recurrent aversion to and avoidance of genital sexual contact with a partner | |

| Female Sexual Arousal Disorder | Persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain adequate lubrication-swelling response | |

| Male Erectile Disorder | Persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain adequate erection | |

| Female Orgasmic Disorder | Persistent or recurrent delay in or absence of orgasm following a normal sexual excitement phase | |

| Male Orgasmic Disorder | Same for males | |

| Premature Ejaculation | Persistent or recurrent ejaculation before or shortly after penetration and before one wants | |

| Dyspareunia | Persistent or recurrent genital pain associated with intercourse | |

| Vaginismus | Persistent or recurrent involuntary spasm of the outer third of the vagina interfering with intercourse | |

| Exhibitionism | Recurrent sexually arousing fantasies, urges, or behaviors involving exposure of one’s genitals to unsuspecting strangers lasting for 6 months or more | |

| Fetishism | Same, but stimulus is a nonliving object | |

| Frotteurism | Same, but stimulus is touching a nonconsenting person | |

| Pedophilia | Same, but stimulus is a child younger than 13, and a patient is at least 16 and at least 5 years older than the child/children | |

| Sexual Masochism | Same, but stimulus is the act of being made to suffer (real, not simulated) | |

| Sexual Sadism | Same, but stimulus is the act of making another suffer (real, not simulated) | |

| Transvestic Fetishism | Same, but stimulus is cross-dressing (With Gender Dysphoria if one has it) | |

| Voyeurism | Same, but stimulus is observing an unsuspecting person naked or during sex | |

| Gender Identity Disorder | 1)Strong persistent cross-gender identification, in children has to have 4 or more of:- repeatedly stated desire to be or insistence that one is the other sex- preference for cross-dressing- preference for cross-sex roles in play or fantasies of being the other sex- desire to participate in stereotypic games and pastimes of the other sexstrong preference for playmates of the other sex2)Persistent discomfort with one’s sex or gender role3)Disturbance not concurrent with physical intersex condition | |

| Sleep Disorders | Primary Insomnia | Difficulty initiating/maintaining or nonrestorative sleep for over 1 month |

| Primary Hypersomnia | Excessive sleepiness (either prolonged or daytime sleep almost every day) for >1 month; Recurrent if episodes last 3 days or more several times a year for 2 years or more | |

| Narcolepsy | Irresistible attacks of refreshing sleep daily for 3 months or moreOne or more of:Cataplexy (brief sudden bilateral loss of muscle tone)REM elements intrusion into sleep-wakefulness transitions (hypnopompic or hypnagogic hallucinations or sleep paralysis), or both | |

| Breathing-Related Sleep Disorder | Sleep disruption due to a sleep-related breathing condition leading to excessive sleepiness or insomnia | |

| Circadian Rhythm Sleep DisorderTypes: Delayed Sleep Phase, Jet Lag, Shift Work, and Unspecified | Sleep disruption due to a mismatch between one’s schedule and one’s circadian sleep-wake pattern leading to excessive sleepiness or insomnia | |

| Nightmare Disorder | 1)Repeated awakening from nightmares with detailed recall of their content (usually during second half of the sleep period)2)On awakening one rapidly becomes oriented and alert | |

| Sleep Terror Disorder | 1) Recurrent abrupt awakening with a panicky scream (usually during first third of the sleep period)2) Intense fear and signs of autonomic arousal during each episode3) Relative unresponsiveness to comforting4) No dream is recalled and there is amnesia for the episode | |

| Sleepwalking Disorder | 1) Recurrent raising from bed and walking about during sleep (usually during first third of the sleep period)2) During episodes one has a blank staring face and is relatively unresponsive to attempts to communicate or wake one up3) On awakening one has amnesia for the episode4) Confusion and disorientation upon awakening from the episode lasts no more then a few minutes | |

| Impulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Specified | Intermittent Explosive Disorder | 1) Several discrete episodes of failure to resist aggressive impulses resulting in serious assaultive acts or destruction of property2) Aggressiveness is grossly out of proportion to the precipitant |

| Kleptomania | 1) Recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects that are not needed2) Increasing sense of tension before theft3) Pleasure/gratification/relief during theft4) Theft does not express anger or vengeance and is not in response to delusions or hallucinations | |

| Pyromania | 1)Recurrent deliberate fire setting2)Tension or affective arousal before the act3)Fascination with fire and its situational context4)Pleasure/gratification/relief while setting fire or witnessing its aftermath5)No realistic purpose or delusions/hallucinations or expressing of anger or vengeance explain fire setting | |

| Pathological Gambling | Recurrent maladaptive gambling indicated by 5 or more of:1) is preoccupied with gambling2) needs to gamble with increasing amounts of money to achieve desired excitement3) has repeated unsuccessful efforts to control or stop gambling4) is restless or irritable when attempting to quit5) uses gambling to escape problems or relieve dysphoric mood6) after loosing money returns to get even7) lies to others to conceal the extent of gambling8) commits illegal acts to finance gambling9) jeopardizes relationships/jobs because of gambling10) relies on others to provide money to relieve a desperate financial situation caused by gambling | |

| Trichotillomania | 1)Recurrent pulling out of one’s hair resulting in noticeable hair loss2)Increasing sense of tension before pulling out the hair3)Pleasure/gratification/relief during pulling out the hair | |

| Adjustment Disorders | Adjustment DisorderAcute if less than 6 months, Chronic if over 6) | 1)In response to an identifiable stressor 1 or more of:- distress in excess of what would be expected- significant impairment in functioning2)Occurs within 3 months of the onset of the stressor3)Once the stressor or its consequences terminate, symptoms do not persist over 6 months |

C. Implications for treatment:

Detailed discussion of treatment of these conditions is well beyond the scope of this workshop. I would like to mention that milieu treatment becomes more important in geriatric population, since it allows people to fill empty spaces left by their dead friends and relatives and provides structure helping to compensate for cognitive decline. Ways to make sense of one’s life, such as journals and photo albums, are somewhat unusual interventions which are often effective in psychotherapy with geriatric population.

V. Interaction between various domains of functioning with diagnostic and treatment implications.

A. When evaluating for psychiatric disorders, correct tests for following influences of brain damage proper:

(1) Informally one can check if the client can read, if they read the entire page (without, for example, ignoring its left side), if they recognize objects in the room, walk without deviating to one side and dress without forgetting buttons or buckles on one side.

(2) Constriction of the information in the response;

(3) Stimulus boundedness;

(4) Seeking structure in stimuli;

(5) Rigid fragmentation (concentrating on a part of the stimulus and being unable to let go of it);

(6) Simplification;

(7) Confusion;

(8) Confabulation;

(9) Hesitancy;

(10) Perseveration;

(11) Disinhibition.

B. When evaluating for dementia, correct tests for following influences of psychiatric disorders:

(1) Depression: low motivation, poor concentration, subjective perception of cognitive decline, psychomotor retardation, fatigue;

(2) Mania: poor concentration, psychomotor agitation, disinhibition;

(3) Anxiety: poor concentration, tremors, paresthesias, psychomotor agitation, ruminative intrusive thoughts;

(4) Psychosis: alogia, avolition, disorganization, tangentiality, inappropriate level of abstraction.

C. Implications for treatment:

In general terms, we treat problems caused by organic impairments by structural and environmental interventions, functional problems by medications and psychotherapy, and the combination – by the combination of the above. The examples below will illustrate these points.